Kill It and Leave This Town is one of the 27 animated features that has qualified for this year’s Oscar category. It’s the culmination of a 14-year passion project for director Mariusz Wilczyński, who shares fascinating details about the inspirations and making of, as he declares, “the first feature animated art film in the history of Polish cinema.” This interview was conducted as an Email Q&A.

Jackson Murphy: What is the specific meaning of the title – is it a reaction to your many years of making the movie?

Mariusz Wilczyński: The title Kill It and Leave This Town, as the film itself, has multiple meanings and levels. Its basic meaning is the reason why I made this film in the first place. I felt guilty that I failed to take care of my elderly parents as I was always busy doing my own things. I felt remorse that I had not hugged them before they died. I had not bid farewell. I never finished some conversations. I wanted to meet them once again in Kill It and Leave This Town. I drew them to make up for all these things. People who saw my film have written to me saying that they improved their relationships with parents thanks to the film. They tend to call them more often now, visit them if they can, take better care of them. I believe that thanks to that, I managed to kill that sense of guilt inside me. That is the main reason why I made my film. Kill It and Leave This Town: kill all these things that torment you, the ones that stem from something that you broke in your life, and fix it. The other meaning is, actually, the one that you mention in your question – it is the process of drawing the film. I had never expected that it would take 14 years, a quarter of my life. On the one hand, I believe it was the most meaningful time of my life when I was so delighted to do something so important for me. On the other hand, I took so long that I was dying to finish the film, kill everything there was in it, and liberate myself. I succeeded, and I feel free at last.

JM: You break all kinds of rules when it comes to animation, and the results are fantastic and fascinating. Was this one of your intentions at the beginning of this process?

MW: To answer your question, I have to tell you the story of how I became a film-drawing artist because this is why my films are so different from others. I was a painter, and at some point, when I was already 35, I fell in love with animation. I left behind quite a promising career in painting and decided to draw, to learn how to do it. I made two crucial resolutions, which I have stuck to ever since. The first was not to follow what other animation artists are doing – I decided not to watch it. The other resolution was that I would not read any books about the technology of animation. I wanted to discover it all by myself. It turned out to be the best possible choice for me. I had never thought that I would have a career in animation, that I would be a director. I never submitted my films to festivals – I had been keeping them in a sock drawer. Not that long ago, Chris Robinson, director of Ottawa International Animation Festival, asked me: “Why am I not familiar with any of your films? It is fantastic. I want to do a retrospective.” And I replied: “You know, Chris, I never used to submit them to any festivals.” Chris could not believe it – I had just won Grand Prix for Best Animated Feature at the festival in Ottawa, and it seemed quite improbable that the guy who won the festival would lock his works in the sock drawer. I never thought of having a great career in animation – I treated it as the most beautiful adventure of my life. That was the beauty of it: at thirty-five, I fell in love and embarked on an adventure only children can experience. It was an inexplicable joy. When I am making a film, I take a particular approach. I spent 14 years working on Kill It and Leave This Town, and my goal was not to make a product with a title. I did not think that I had to do it in 4 years and then the next film in the following five years, and yet another one, and so on. Work served as a kind of meditation. It let me contemplate the topics that my film deals with, like the meaning of life, the departure of my parents and friends who passed away. I worked so long on this film, and I believe this is why it is so unlike any other because I never attempted to make a film for the theaters in the first place.

JM: The artwork / symbols / cut-outs / mixed media / proportions are incredibly unique, especially involving the train and the town. Which visual aspects were the most difficult to create?

MW: I always try to create something I have not done before. That is why, in all the formal solutions, we were coming up with some new ways. Of course, everything is based on my drawings. I drew all the scenery and characters by hand, but we had to devise some new ideas when it went further than just the picture. For example, we ordered some tiny customized neons that we lit up. All the lights and neons were handmade, as well as the glass with the water flowing down. We did not use computers for that. When the train passes by, you can see the landscapes changing in its window. These were also hand-drawn by me, and next, we adjusted the lighting in analog. Only later did we use the greenbox to put it all together. Everything was equally fascinating and challenging. All these solutions were new – I had never done this before, and I had to come up with something. I had to become a bit of a scientist who devises an idea to make things run. That is how I always work on my films. First, I think of what the film should be about, and then I think up all these magic machines that help me make it come to life.

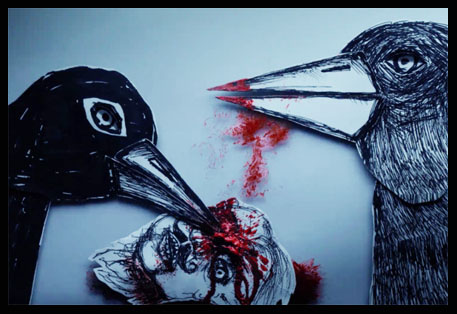

JM: There are some grotesque sequences. What was your checklist for crafting them?

MW: I found it crucial not to terrorize and overwhelm the viewer with such a serious film. I did not want the audience to feel unsure of what to do. That is what life is like – happiness and sadness intertwine all the time. At the stage of composing the whole film, when I had already had the scenes, I would often remember some amusing stories from my life or funny conversations I had with my grandparents and mom, and I recreated them into dialogues. I believe this is a very natural way to work for the writers, for example.

JM: I love the visual of the brains connecting to the telephone/power wires. How did you come up with that?

MW: There are some scenes in my film that I do not fully understand. They are the ones that came to me in my dreams. I intuitively feel what they mean, but I fail to describe it in words. It would be possible if I were a haiku poet. If Mark Rothko was asked to explain the meaning of two juxtaposed different hues of red color, which are almost as strong as a philosophical treatise, he would cease to do it either. That is true also for the film: you create some scenes which you cannot entirely understand, but you know what you want to express with them. I had been wondering how to present a meaningful thread in my film. We can see that the supernatural, unreal forces, which exist in maybe the 8th or the 11th dimension, get in touch with us and affect our life here, on Earth. For a long time, I was in a trance I could even call delirium, where I tried to think and create it all. I was looking for a way to do it. I intuitively drew, and I also kept a sort of a sleep journal on my nightstand. Whenever something came to me in my sleep, I put it there. I do not think it is possible to find an explanation for everything. Mark Rothko would not probably be able to explain the significance of vermillion and carmine in his works. John Coltrane or Miles Davis would have problems describing what the meaning of a given part is. Yet, the sound of Davis’s trumpet does have the meaning. We know we follow him right into space, but he was not able to explain this. I believe this is the secret of art, the secret of these non-verbal ways to communicate.

JM: How challenging was it to incorporate you/your alter ego as a prominent character?

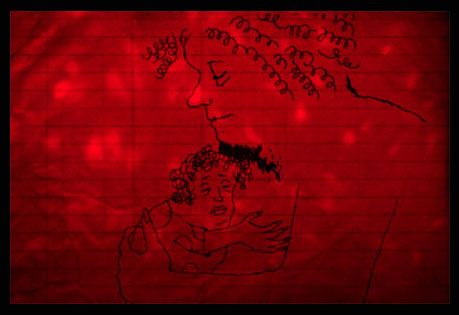

MW: It was very natural since the film tells a story about my parents and my friend Tadeusz Nalepa, whose music you can hear in the soundtrack, and about what I went through. It is not my biography. It is a tale based on my emotions, on my life, so it is mine, indeed. It seemed natural to draw myself in the film. To do it, I had to break through inner shame. I knew that some conventionality is involved in drawing – it allows you to stray from being literal and create some poetic distance from reality. Nonetheless, these moments were difficult for me. For example, the scene of my last conversation with my mother was emotionally challenging. I had to depict my abrasiveness and indifference to the disease and suffering of my mother. I am not a bad child, yet I cannot hear and see because I am so immersed in my own world. Similarly, but for different reasons, I found it challenging to draw myself as a giant Gulliver, walking through town naked, with small houses that barely reach up to my belly button. I am naked throughout the film. I found it awkward in all my bashfulness. Still, I tried to picture it naturally, avoiding being unnecessarily intrusive. It is how we come to this world – naked. I thought this can serve as proof that my film is honest and authentic.

JM: How passionate are you about using light and shadows in conveying action and emotions in a scene?

MW: This might be the most important thing for me. I spent hundreds of hours on it. I wished to show my whole film in the magic hour. I wanted to keep it dark because then these everyday things become transcendental. Darkness allows the ghosts to emerge, and there are many of them in my film. I love the magic hour, and it seemed to be the best moment. That is why I set the whole story at some strange dawn that cannot turn into day. Or it is dusk that cannot become a night. The only parts of the movie with a lot of light take place at the seaside. It is a reminiscence of my childhood memory. I first left my tar-covered hometown full of chimneys when my mom and I took the train to the seaside. I was six at the time, and I can vividly remember that we fell asleep on the train. As soon as I woke up, when we arrived at the station, I saw a beam of light, felt the breeze, the power of nature, the infinite horizon, the sea. At that moment, I realized that there are a different sky and a different view from the one I had seen in my beloved industrial hometown of Łódź.

JM: You make some cool music choices. What were your goals with the music?

MW: The choice of music for the soundtrack came to me as something natural. The author of the music you hear in the film was Tadeusz Nalepa, one of its heroes. Tadeusz was my close friend, to whom “Kill It and Leave This Town” is also partly dedicated. He was the most important man in my life. In a way, he took the role of a father figure, but he was mostly my friend and my mentor. I knew what Tadeusz sings about exactly in certain songs. Therefore, I featured them in the particular scenes so that his voice and lyrics accompany and prolong the narrative. It is quite significant. The narration of my film is in some parts based on dialogues. Other times it is based on the plot, and sometimes – on the songs. They do not serve as an addition or a background. They lead the film further on through the words sung by Tadeusz. There is always a guide that helps find the way through the emotions – these are the dialogues, the drawings I made, or the songs by Tadeusz. He is one of the most meaningful narrators in my film.

JM: This film is a major achievement for Poland, making history. What significance does this have on you?

MW: I live in a forest, at some distance from the city, and I tend to live at my own pace. It does not fully get to me, maybe also due to the pandemic. Under normal circumstances, I would probably fly around the world and visit numerous festivals. I would have conversations with people, which is extremely important. We would take part in the screenings together. I would receive the awards on stage, and probably only then would I feel that. But here I am now, sitting in my study. I see that all the journeys I am embarking on with Kill It and Leave This Town are happening on my laptop screen. Everything seems so unreal. This life that we are having online does not give me this sense of awareness of success. Well, maybe, when I go to the local grocery store to get my milk and rolls, some people approach me and congratulate me. Then I do have the feeling that something happened. But all in all, nothing has changed. Moreover, I am almost 60, and it is too late for the success to go into my head. I am just happy that my film became a significant thing for many people.

JM: You’re Oscar qualified in a very unique year for animation. What would a nomination mean to you?

MW: Kill It and Leave This Town is unlike any other animated feature film. It is distinct, different, dirty, doodled all over, and it poses difficult questions. Usually, people expect animation to be pretty, pleasant, preferably an eye-candy for children. My film is unattractive, unsettling, dedicated strictly to a mature adult audience. Yet, should the miracle happen, and we get the nomination, it would be very significant, not only for the film itself, but also for the field of art that is not aimed at creating nice and pretty objects, but asking difficult, uncomfortable questions instead. These questions open the viewer to some reflection and force them to look for the answers. That would be an incredible thing, and I would feel shocked and delighted. Other aspects related to the nomination, like recognition, do not mean that much to me.

- INTERVIEW: Jeff Fowler On “Knuckles” And “Sonic 3” - April 22, 2024

- INTERVIEW: “Inside Out 2” Director And Producer On Pixar Sequel - April 16, 2024

- INTERVIEW: “Puffin Rock And The New Friends” And 25 Years Of Cartoon Saloon - April 10, 2024

February 10th, 2021

February 10th, 2021  Jackson Murphy

Jackson Murphy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: