Although he would be horrified to have his work linked to Sausage Party and The Emoji Movie, Winsor McCay deserves the title of father of animation. He didn’t make the first animated films, but he was the first to suggest the real potential of the medium. The art of character animation can be traced to Little Nemo and Gertie the Dinosaur.

Yet McCay is not the household name he deserves to be. In France, there are streets and schools named for Georges Méliès, Emil Cohl and Émil Reynaud; in Japan, there are museums dedicated to the work of Osamu Tezuka, Studio Ghibli and other animation and manga artists. There is no McCay College of Art or McCay Museum or Winsor McCay Street in Washington or New York or Hollywood. The Simpsons, Bugs Bunny, Cruella de Vil, Woody, Jessie and Scooby-Doo have appeared on US postage stamps, but not Gertie. ( “Little Nemo” was included in a series of stamps honoring comic strips.)

McCay’s unmatched draftsmanship made him a key figure not only in the history of animation, but of comic strips and editorial cartoons. At a time when even commercial artists were highly trained masters of pen and ink, McCay simply drew rings around everyone else.

In 1903, McCay drew his first comic strip, “Tales of the Jungle Imps by Felix Fiddle.” It caught the eye of James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the flamboyant publisher of the New York Herald and Evening Telegra. He brought the artist to New York, where McCay scored his first big hit with “Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend”in 1905. Later that year, he began his masterpiece, “Little Nemo in Slumberland,” which explored other dream worlds. Many historians of the comics rank “Nemo” second only to George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat.”

His strips’ popularity enabled McCay to create a vaudeville act for himself in 1906. He drew panels of “Rarebit Fiend” and “Little Nemo” on a chalkboard with astonishing speed—and no underdrawing. He sketched members of the audience and took the faces of a baby boy and girl through childhood, maturity and old age by adding and erasing lines.

McCay made 4,000 drawings for the film of “Little Nemo,” working in India ink on translucent rice paper. When he premiered the film in his act in 1911, audiences didn’t know what to make of Little Nemo. No one had ever seen anything like it because there had never been anything like it. Animation pioneers J. Stuart Blackton and Emil Cohl had drawn simple line figures performing elementary motions. McCay depicted rounded characters moving smoothly through three-dimensional space. To the artist’s chagrin, viewers assumed he had used trick photography of live actors.

Perhaps the disbelief that greeted Nemo and How a Mosquito Operates (1912) led McCay to chose a subject that couldn’t be faked for his third film. More than a century after its debut, Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) remains one of the seminal films in history animation. Gertie is not just any dinosaur, but very specific one, with an endearing, if childish, personality which she demonstrates through her movements—the insouciant way she scratches her chin with the tip of her tail, the tears she sheds when McCay scolds her. McCay achieved a level of draftsmanship and fluid movement would stand for 20 years—until Walt Disney’s artists began hitting their stride in the early 1930’s.

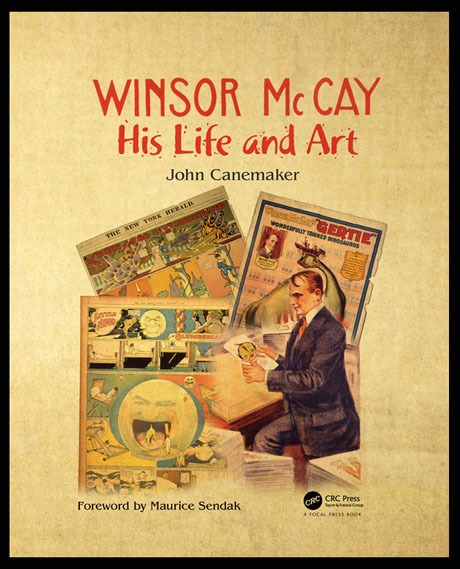

There is only one complete biography of the artist, and fortunately, it’s a gem. John Canemaker’s Winsor McCay: His Life and Art, originally published in 2005, has just been re-issued in an expanded edition by CRC Press.

Canemaker studied McCay’s work for decades. He filmed John Fitzsimmons, whom McCay had hired as a teen-ager to trace the backgrounds in Gertie for his documentary Remembering Winsor McCay (1976). Over the years he tracked down documents, interviewed family members, examined original artwork and read old articles with a perseverance Nancy Drew might envy.

This edition includes some interesting new material. McCay’s birth date has been listed as 1867, 1868, 1869 and 1871. Canemaker includes material from two researchers who offer their own answers, while showing how they interpret fragmentary evidence to reach their conclusions. It’s an interesting lesson in genealogical research.

Other additions include a Variety review of How a Mosquito Operates from 1913 (the critic dismisses the film as “very disgusting and creepy”) and an expanded account of the premiere of Gertie, with notes from animation historian Donald Crafton. The more detailed discussion of the salvage and restoration of McCay’s films and their negatives reminds readers how easily these monumental works could have been lost.

Winsor McCay: His Life and Art belongs on the bookshelf of anyone interested in animation. Completionists and younger readers who don’t already own a copy should pick up the new edition, a.s.a.p

Winsor McCay: His Life and Art by John Canemaker

CRC Press/Focal Press: $59.95; 284 pp.

- Charles Solomon’s Animation Year End Review 2023 - December 28, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Makoto Shinkai on “Suzume” - November 27, 2023

- Interesting Portrayals of Gay Men in Manga/Anime - June 12, 2023

September 21st, 2018

September 21st, 2018  Charles Solomon

Charles Solomon  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: