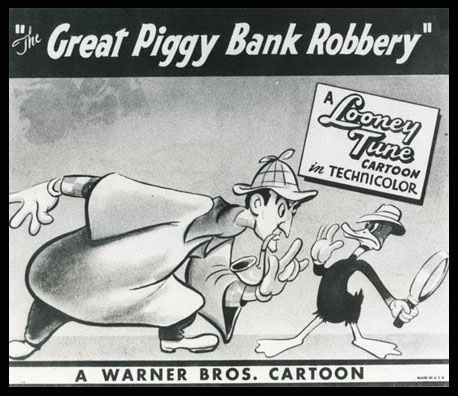

Before there was the term “fandom,” there was The Great Piggy Bank Robbery. In this classic Warner Bros cartoon short, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this month, none other than Daffy Duck proves to be a comic book “fanboy’ (or is it “fanduck?”).

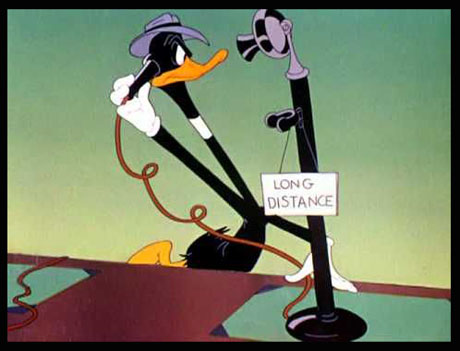

As The Great Piggy Bank Robbery opens, Daffy is on the farm where he lives, impatiently waiting at the mailbox for his latest Dick Tracy comic book. The fictional detective, created by artist Chester Gould, celebrates an anniversary this year as well, as he debuted 90 years ago this fall. When The Great Piggy Bank Robbery was produced, Dick Tracy was hugely popular, with a devoted following, which here includes Daffy, who declares, as he waits, “I can hardly wait to see what happens to Dick Tracy! I love that man!”

When the mail arrives, Daffy rifles through all of the letters before grabbing his Dick Tracy comic, after which he heads to the back of the barn to read it. Inspired by the actions of Tracy himself, Daffy begins to act as if he is the detective, accidentally knocking himself out.

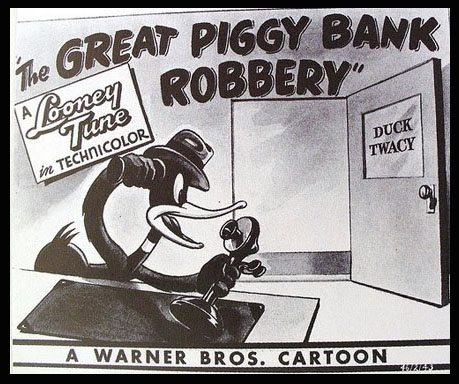

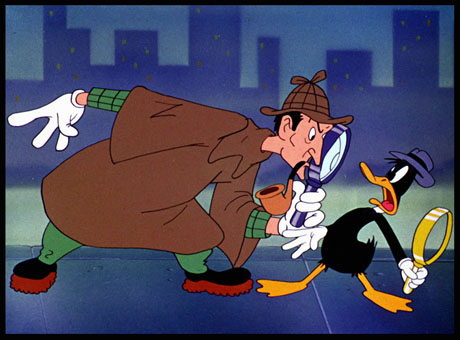

This leads to a dream sequence, where Daffy is now the great detective “Duck Twacy.” He discovers a crime wave in which piggy banks (including his) are being stolen all over town. He goes out in search of the criminal behind it and runs into Sherlock Holmes (“Scram Sherlock! I’m working this side of the street!,” Daffy yells).

Twacy is able to track down the villains by jumping on a trolly car (being driven by Porky Pig, in a cameo) with its destination reading: “To Gangster Hideout.”

Twacy encounters the gamut of criminal gangsters at the hideout, each one an exaggerated take on Dick Tracy’s “Rogues’ Gallery,” of villains with unique physical appearances, which were a staple of the comic. In The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, there’s “Snake Eyes” (a parody of the character “B.B. Eyes” from the comic) and “Pickle Puss” (a parody of the comic’s “Pruneface’).

The short also includes a long list of hysterically creative baddies. There is the literal “Hammerhead,” “Pussycat Puss,” who has a sneaking resemblance to Sylvester, “Neon Noodle,” who Twacy takes on and turns into an “Eat at Joe’s” sign. There’s also “Rubberhead,” who sports a pencil eraser as a head and, in one of the short subject’s biggest laughs, “Batman,” an anthropomorphic baseball bat.

One of the actual villains from the Dick Tracy comics, Flattop, appears briefly in the short, with his head used as an airstrip during the final battle between Twacy and the gangsters.

The piggy banks are recovered, and as Twacy begins embracing his bank, he awakes from his dream to find himself back on the farm, hugging a pig in the mud, who declares, “I just love that duck!”

At the helm for The Great Piggy Bank Robbery was the brilliant director Robert Clampett, who packs so much story, artistry, character, and comedy into this short that it’s no wonder it earned the number 16 spot in Jerry Beck’s 1994 book, The 50 Greatest Cartoons.

It’s fitting that this short subject, which is all about “fandom,” has a rich “fandom” all its own, seventy-five years after its debut on July 20, 1946.

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery also influenced a generation of artists, including John Kricfalusi, creator of The Ren & Stimpy Show. In the book, The 50 Greatest Cartoons, Kricfalusi notes that after he first saw the short, “I thought it was the best cartoon that man had ever produced.”

Also, in The 50 Greatest Cartoons, contributor Steve Schneider sums up Clampett’s work perfectly, writing: “Robert Frost said that the poet’s principal mission is to come up with words that stick – to conjure those visions and constructions that, somehow, stay with people, making the ephemeral language something enduring and strong, with the power to change lives. Applying this principle, Bob Clampett’s forever priceless The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is clearly a work of the highest cinematic poetry, for prompting the film’s manic hilarity are the sequences of images that remain among the most indelible in cartoon history.”

- An Eye for A Classic: The 60th Anniversary of “Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol” - December 22, 2022

- A Very Merry Mickey: The 70th Anniversary of “Pluto’s Christmas Tree” - December 19, 2022

- A Fine French Feline Film: The 60th Anniversary of “Gay Pur-ee” - December 12, 2022

July 30th, 2021

July 30th, 2021  Michael Lyons

Michael Lyons  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: